Quantum computers are about to get real

Although the term “quantum computer” might suggest a miniature, sleek device, the latest incarnations are a far cry from anything available in the Apple Store. In a laboratory just 60 kilometers north of New York City, scientists are running a fledgling quantum computer through its paces — and the whole package looks like something that might be found in a dark corner of a basement. The cooling system that envelops the computer is about the size and shape of a household water heater.

Beneath that clunky exterior sits the heart of the computer, the quantum processor, a tiny, precisely engineered chip about a centimeter on each side. Chilled to temperatures just above absolute zero, the computer — made by IBM and housed at the company’s Thomas J. Watson Research Center in Yorktown Heights, N.Y. — comprises 16 quantum bits, or qubits, enough for only simple calculations.

If this computer can be scaled up, though, it could transcend current limits of computation. Computers based on the physics of the supersmall can solve puzzles no other computer can — at least in theory — because quantum entities behave unlike anything in a larger realm.

Quantum computers aren’t putting standard computers to shame just yet. The most advanced computers are working with fewer than two dozen qubits. But teams from industry and academia are working on expanding their own versions of quantum computers to 50 or 100 qubits, enough to perform certain calculations that the most powerful supercomputers can’t pull off.

The race is on to reach that milestone, known as “quantum supremacy.” Scientists should meet this goal within a couple of years, says quantum physicist David Schuster of the University of Chicago. “There’s no reason that I see that it won’t work.”

But supremacy is only an initial step, a symbolic marker akin to sticking a flagpole into the ground of an unexplored landscape. The first tasks where quantum computers prevail will be contrived problems set up to be difficult for a standard computer but easy for a quantum one. Eventually, the hope is, the computers will become prized tools of scientists and businesses.

Attention-getting ideas

Some of the first useful problems quantum computers will probably tackle will be to simulate small molecules or chemical reactions. From there, the computers could go on to speed the search for new drugs or kick-start the development of energy-saving catalysts to accelerate chemical reactions. To find the best material for a particular job, quantum computers could search through millions of possibilities to pinpoint the ideal choice, for example, ultrastrong polymers for use in airplane wings. Advertisers could use a quantum algorithm to improve their product recommendations — dishing out an ad for that new cell phone just when you’re on the verge of purchasing one.

Quantum computers could provide a boost to machine learning, too, allowing for nearly flawless handwriting recognition or helping self-driving cars assess the flood of data pouring in from their sensors to swerve away from a child running into the street. And scientists might use quantum computers to explore exotic realms of physics, simulating what might happen deep inside a black hole, for example.

But quantum computers won’t reach their real potential — which will require harnessing the power of millions of qubits — for more than a decade. Exactly what possibilities exist for the long-term future of quantum computers is still up in the air.

The outlook is similar to the patchy vision that surrounded the development of standard computers — which quantum scientists refer to as “classical” computers — in the middle of the 20th century. When they began to tinker with electronic computers, scientists couldn’t fathom all of the eventual applications; they just knew the machines possessed great power. From that initial promise, classical computers have become indispensable in science and business, dominating daily life, with handheld smartphones becoming constant companions (SN: 4/1/17, p. 18).

Since the 1980s, when the idea of a quantum computer first attracted interest, progress has come in fits and starts. Without the ability to create real quantum computers, the work remained theoretical, and it wasn’t clear when — or if — quantum computations would be achievable. Now, with the small quantum computers at hand, and new developments coming swiftly, scientists and corporations are preparing for a new technology that finally seems within reach.

“Companies are really paying attention,” Microsoft’s Krysta Svore said March 13 in New Orleans during a packed session at a meeting of the American Physical Society. Enthusiastic physicists filled the room and huddled at the doorways, straining to hear as she spoke. Svore and her team are exploring what these nascent quantum computers might eventually be capable of. “We’re very excited about the potential to really revolutionize … what we can compute.”

Anatomy of a qubit

Quantum computing’s promise is rooted in quantum mechanics, the counterintuitive physics that governs tiny entities such as atoms, electrons and molecules. The basic element of a quantum computer is the qubit (pronounced “CUE-bit”). Unlike a standard computer bit, which can take on a value of 0 or 1, a qubit can be 0, 1 or a combination of the two — a sort of purgatory between 0 and 1 known as a quantum superposition. When a qubit is measured, there’s some chance of getting 0 and some chance of getting 1. But before it’s measured, it’s both 0 and 1.

Because qubits can represent 0 and 1 simultaneously, they can encode a wealth of information. In computations, both possibilities — 0 and 1 — are operated on at the same time, allowing for a sort of parallel computation that speeds up solutions.

Another qubit quirk: Their properties can be intertwined through the quantum phenomenon of entanglement (SN: 4/29/17, p. 8). A measurement of one qubit in an entangled pair instantly reveals the value of its partner, even if they are far apart — what Albert Einstein called “spooky action at a distance.”

Such weird quantum properties can make for superefficient calculations. But the approach won’t speed up solutions for every problem thrown at it. Quantum calculators are particularly suited to certain types of puzzles, the kind for which correct answers can be selected by a process called quantum interference. Through quantum interference, the correct answer is amplified while others are canceled out, like sets of ripples meeting one another in a lake, causing some peaks to become larger and others to disappear.

One of the most famous potential uses for quantum computers is breaking up large integers into their prime factors. For classical computers, this task is so difficult that credit card data and other sensitive information are secured via encryption based on factoring numbers. Eventually, a large enough quantum computer could break this type of encryption, factoring numbers that would take millions of years for a classical computer to crack.

Quantum computers also promise to speed up searches, using qubits to more efficiently pick out an information needle in a data haystack.

Qubits can be made using a variety of materials, including ions, silicon or superconductors, which conduct electricity without resistance. Unfortunately, none of these technologies allow for a computer that will fit easily on a desktop. Though the computer chips themselves are tiny, they depend on large cooling systems, vacuum chambers or other bulky equipment to maintain the delicate quantum properties of the qubits. Quantum computers will probably be confined to specialized laboratories for the foreseeable future, to be accessed remotely via the internet.

Going supreme

That vision of Web-connected quantum computers has already begun to Quantum computing is exciting. It’s coming, and we want a lot more people to be well-versed in itmaterialize. In 2016, IBM unveiled the Quantum Experience, a quantum computer that anyone around the world can access online for free.

With only five qubits, the Quantum Experience is “limited in what you can do,” says Jerry Chow, who manages IBM’s experimental quantum computing group. (IBM’s 16-qubit computer is in beta testing, so Quantum Experience users are just beginning to get their hands on it.) Despite its limitations, the Quantum Experience has allowed scientists, computer programmers and the public to become familiar with programming quantum computers — which follow different rules than standard computers and therefore require new ways of thinking about problems. “Quantum computing is exciting. It’s coming, and we want a lot more people to be well-versed in it,” Chow says. “That’ll make the development and the advancement even faster.”

But to fully jump-start quantum computing, scientists will need to prove that their machines can outperform the best standard computers. “This step is important to convince the community that you’re building an actual quantum computer,” says quantum physicist Simon Devitt of Macquarie University in Sydney. A demonstration of such quantum supremacy could come by the end of the year or in 2018, Devitt predicts.

Researchers from Google set out a strategy to demonstrate quantum supremacy, posted online at arXiv.org in 2016. They proposed an algorithm that, if run on a large enough quantum computer, would produce results that couldn’t be replicated by the world’s most powerful supercomputers.

The method involves performing random operations on the qubits, and measuring the distribution of answers that are spit out. Getting the same distribution on a classical supercomputer would require simulating the complex inner workings of a quantum computer. Simulating a quantum computer with more than about 45 qubits becomes unmanageable. Supercomputers haven’t been able to reach these quantum wilds.

To enter this hinterland, Google, which has a nine-qubit computer, has aggressive plans to scale up to 49 qubits. “We’re pretty optimistic,” says Google’s John Martinis, also a physicist at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Martinis and colleagues plan to proceed in stages, working out the kinks along the way. “You build something, and then if it’s not working exquisitely well, then you don’t do the next one — you fix what’s going on,” he says. The researchers are currently developing quantum computers of 15 and 22 qubits.

IBM, like Google, also plans to go big. In March, the company announced it would build a 50-qubit computer in the next few years and make it available to businesses eager to be among the first adopters of the burgeoning technology. Just two months later, in May, IBM announced that its scientists had created the 16-qubit quantum computer, as well as a 17-qubit prototype that will be a technological jumping-off point for the company’s future line of commercial computers.

But a quantum computer is much more than the sum of its qubits. “One of the real key aspects about scaling up is not simply … qubit number, but really improving the device performance,” Chow says. So IBM researchers are focusing on a standard they call “quantum volume,” which takes into account several factors. These include the number of qubits, how each qubit is connected to its neighbors, how quickly errors slip into calculations and how many operations can be performed at once. “These are all factors that really give your quantum processor its power,” Chow says.

Errors are a major obstacle to boosting quantum volume. With their delicate quantum properties, qubits can accumulate glitches with each operation. Qubits must resist these errors or calculations quickly become unreliable. Eventually, quantum computers with many qubits will be able to fix errors that crop up, through a procedure known as error correction. Still, to boost the complexity of calculations quantum computers can take on, qubit reliability will need to keep improving.

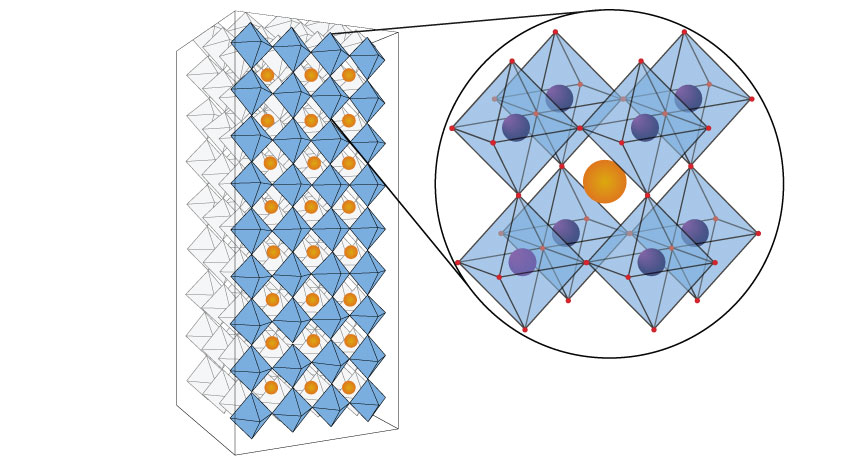

Different technologies for forming qubits have various strengths and weaknesses, which affect quantum volume. IBM and Google build their qubits out of superconducting materials, as do many academic scientists. In superconductors cooled to extremely low temperatures, electrons flow unimpeded. To fashion superconducting qubits, scientists form circuits in which current flows inside a loop of wire made of aluminum or another superconducting material.

Several teams of academic researchers create qubits from single ions, trapped in place and probed with lasers. Intel and others are working with qubits fabricated from tiny bits of silicon known as quantum dots (SN: 7/11/15, p. 22). Microsoft is studying what are known as topological qubits, which would be extra-resistant to errors creeping into calculations. Qubits can even be forged from diamond, using defects in the crystal that isolate a single electron. Photonic quantum computers, meanwhile, make calculations using particles of light. A Chinese-led team demonstrated in a paper published May 1 in Nature Photonics that a light-based quantum computer could outperform the earliest electronic computers on a particular problem.

One company, D-Wave, claims to have a quantum computer that can perform serious calculations, albeit using a more limited strategy than other quantum computers (SN: 7/26/14, p. 6). But many scientists are skeptical about the approach. “The general consensus at the moment is that something quantum is happening, but it’s still very unclear what it is,” says Devitt.

Identical ions

While superconducting qubits have received the most attention from giants like IBM and Google, underdogs taking different approaches could eventually pass these companies by. One potential upstart is Chris Monroe, who crafts ion-based quantum computers.

On a walkway near his office on the University of Maryland campus in College Park, a banner featuring a larger-than-life portrait of Monroe adorns a fence. The message: Monroe’s quantum computers are a “fearless idea.” The banner is part of an advertising campaign featuring several of the university’s researchers, but Monroe seems an apt choice, because his research bucks the trend of working with superconducting qubits.

Monroe and his small army of researchers arrange ions in neat lines, manipulating them with lasers. In a paper published in Nature in 2016, Monroe and colleagues debuted a five-qubit quantum computer, made of ytterbium ions, allowing scientists to carry out various quantum computations. A 32-ion computer is in the works, he says.

Monroe’s labs — he has half a dozen of them on campus — don’t resemble anything normally associated with computers. Tables hold an indecipherable mess of lenses and mirrors, surrounding a vacuum chamber that houses the ions. As with IBM’s computer, although the full package is bulky, the quantum part is minuscule: The chain of ions spans just hundredths of a millimeter.

Scientists in laser goggles tend to the whole setup. The foreign nature of the equipment explains why ion technology for quantum computing hasn’t taken off yet, Monroe says. So he and colleagues took matters into their own hands, creating a start-up called IonQ, which plans to refine ion computers to make them easier to work with.

Monroe points out a few advantages of his technology. In particular, ions of the same type are identical. In other systems, tiny differences between qubits can muck up a quantum computer’s operations. As quantum computers scale up, Monroe says, there will be a big price to pay for those small differences. “Having qubits that are identical, over millions of them, is going to be really important.”

In a paper published in March in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Monroe and colleagues compared their quantum computer with IBM’s Quantum Experience. The ion computer performed operations more slowly than IBM’s superconducting one, but it benefited from being more interconnected — each ion can be entangled with any other ion, whereas IBM’s qubits can be entangled only with adjacent qubits. That interconnectedness means that calculations can be performed in fewer steps, helping to make up for the slower operation speed, and minimizing the opportunity for errors.

Early applications

Computers like Monroe’s are still far from unlocking the full power of quantum computing. To perform increasingly complex tasks, scientists will have to correct the errors that slip into calculations, fixing problems on the fly by spreading information out among many qubits. Unfortunately, such error correction multiplies the number of qubits required by a factor of 10, 100 or even thousands, depending on the quality of the qubits. Fully error-corrected quantum computers will require millions of qubits. That’s still a long way off.

So scientists are sketching out some simple problems that quantum computers could dig into without error correction. One of the most important early applications will be to study the chemistry of small molecules or simple reactions, by using quantum computers to simulate the quantum mechanics of chemical systems. In 2016, scientists from Google, Harvard University and other institutions performed such a quantum simulation of a hydrogen molecule. Hydrogen has already been simulated with classical computers with similar results, but more complex molecules could follow as quantum computers scale up.

Once error-corrected quantum computers appear, many quantum physicists have their eye on one chemistry problem in particular: making fertilizer. Though it seems an unlikely mission for quantum physicists, the task illustrates the game-changing potential of quantum computers.

The Haber-Bosch process, which is used to create nitrogen-rich fertilizers, is hugely energy intensive, demanding high temperatures and pressures. The process, essential for modern farming, consumes around 1 percent of the world’s energy supply. There may be a better way. Nitrogen-fixing bacteria easily extract nitrogen from the air, thanks to the enzyme nitrogenase. Quantum computers could help simulate this enzyme and reveal its properties, perhaps allowing scientists “to design a catalyst to improve the nitrogen fixation reaction, make it more efficient, and save on the world’s energy,” says Microsoft’s Svore. “That’s the kind of thing we want to do on a quantum computer. And for that problem it looks like we’ll need error correction.”

Pinpointing applications that don’t require error correction is difficult, and the possibilities are not fully mapped out. “It’s not because they don’t exist; I think it’s because physicists are not the right people to be finding them,” says Devitt, of Macquarie. Once the hardware is available, the thinking goes, computer scientists will come up with new ideas.

That’s why companies like IBM are pushing their quantum computers to users via the Web. “A lot of these companies are realizing that they need people to start playing around with these things,” Devitt says.

Quantum scientists are trekking into a new, uncharted realm of computation, bringing computer programmers along for the ride. The capabilities of these fledgling systems could reshape the way society uses computers.

Eventually, quantum computers may become part of the fabric of our technological society. Quantum computers could become integrated into a quantum internet, for example, which would be more secure than what exists today (SN: 10/15/16, p. 13).

“Quantum computers and quantum communication effectively allow you to do things in a much more private way,” says physicist Seth Lloyd of MIT, who envisions Web searches that not even the search engine can spy on.

There are probably plenty more uses for quantum computers that nobody has thought up yet.

“We’re not sure exactly what these are going to be used for. That makes it a little weird,” Monroe says. But, he maintains, the computers will find their niches. “Build it and they will come.”